If a utopia is a perfect and ideal world, then a dystopia is well, the opposite. What’s the world coming to? If a dystopia is set in the not-too-distant future, the population is often under the control of a big powerful Somebody who seems to have the best interests of humanity at heart, but who really just wants to keep everybody under thumb. If the dystopia is of the post-apocalyptic kind, there’s usually the chaos of fleeing refugees or a desolate landscape populated by a few struggling survivors. There’s oppression and fear, often some sort of mind-control device, biohazards and disasters natural or man-made galore, but always—lucky for us—one or two rebels who are determined to uncover the truth. Dystopian fiction has deep roots—Aldous Huxley published Brave New World in 1932; Ray Bradbury wrote Fahrenheit 451 in 1953; George Orwell’s classic 1984 dates from 1949; even Lois Lowry’s dystopia for young readers, The Giver, has been around since 1993. Every work of dystopian fiction is unique. There are a myriad number of ways to image the future, but one thing’s for sure: Thinking up the worst is a lot more interesting than thinking up the best.

The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood, 1998, Random House Books, originally published 1985 (Literary Fiction/ Science Fiction)

The United States government has fallen and the righteous Republic of Gilead has taken its place. In Gilead, women need to be protected. They cannot be trusted with money or employment. They must dress modestly and avoid the company of unknown men. They cannot be allowed to read or write; information is too dangerous for the female sex. Women must stay at home, minding the house, reading the Bible, caring for the children. There’s a problem with that last womanly duty though--due to too many chemicals in the body and too much pollution in the air, the birthrate has fallen dramatically. Second marriages and unmarried unions are declared immoral and illegal, and the women involved in any such relationships are rounded up, separated from their families, and—if they’ve given birth before—parceled out to Gilead’s high-ranking Commanders and their childless Wives. These women are only valued for their wombs and if they fail to reproduce, they’re as good as dead. They are the Handmaids of Gilead, and Offred is one of them. The Handmaid’s Tale is her story, her memories of a former life with a husband and daughter, her hints about the events that led to the rise of the Republic, her understanding of Gilead’s rules and crimes, her decisions to trust or fear the Commander, his Wife, the chauffeur, the cook, and the other Handmaids. With The Handmaid’s Tale, author Margaret Atwood spins a tale about the displays of power that can be made with sex, religion, fear, and obedience. Offred’s choices are made painfully clear to the reader; the consequences of her oppressive existence linger long after the last page has been turned.

In The Children of Men, author P.D. James images another future in which birthrates have plummeted. In fact, there hasn’t been a single baby born for nearly twenty years. Children are not the future, and civilization has ground to a halt. War rages, borders are closed, refugees are persecuted, mass suicides are encouraged, desperation is the order of the day. Theo Faron is one man in this barren future, a depressed, ineffectual history professor who happens to be the cousin of the dictator-like Ward of England. Due to his connections, Theo is approached by an underground rebellion called the Fishes, a group that still hopes for a promising future because one of its members—a woman named Julian—is miraculously pregnant. Soon Theo finds himself thrown in with the Fishes as Julian fights to keep her pregnancy secret from the ruthless government. P.D. James is best known for her series of mysteries starring Detective Adam Dalgliesh; The Children of Men and its science fiction tones are a distinct departure for the bestselling writer. But even fans who long for Adam’s return should stick with Theo and Julian—after a slow, deliberate start that chronicles the harsh realities of this futureless future, the drama and the pace pick up and new issues are brought to light. Fans of books-turned-movies should watch 2006’s Children of Men, starring Clive Owen as Theo, Julianne Moore as Julian, and directed by Alfonso Cuarón. The film takes some fascinating liberties with the plot and breaks new cinematic ground; it is a fine companion piece to the novel.

Catching Fire: Book 2 of The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins, 2009, Scholastic Books (Teen Fiction/ Fantasy/ Adventure)

Against all odds, sixteen-year-old Katniss Everdeen won the Hunger Games, the forced battle-to-the-death between twenty-four children from the twelve districts of Panem (the nation formerly known as the United States of America). The Capital holds the Hunger Games every year to remind its citizens of a long-ago failed rebellion, and to make sure the people know exactly who is in charge of not only their lives, but their children's lives as well. Now that she's won, Katniss wants nothing more than to get back to ordinary life, living with her mother and sister and hunting with her stoic friend Gale. But Katniss' win was too unconventional to go unnoticed. To save herself and Peeta, the boy from her district who was also chosen to compete, Katniss pretended to fall in love with Peeta, and that lie broke all the rules. Now Katniss has the attention of the Capital officials and the long-suffering people, and both sides are waiting to see what Katniss will do next. Will she toe the Capital line to ensure the safety of her friends and family, or will she use her rebellion in the Games to spark something bigger? Katniss herself has no idea, but a heart-wrenching tour of the outlying districts and a horrific surprise from the Capital will make up her mind if nothing else does. Catching Fire is the second book in author Suzanne Collin's new trilogy. The first book, 2008's The Hunger Games, focused on Katniss' desperate and action-packed fight for survival. Catching Fire picks up where The Hunger Games left off and opens the story up from the stadium of the Games to the ins and outs of the larger world outside, with a detailed and suspenseful focus on the politics of this under-the-thumb dystopian world. Catching Fire is just as thrilling and gripping as The Hunger Games and with even more to think about. We can only wait with breaths held for the third book to find out how Katniss' superbly told fight turns out.

Catching Fire: Book 2 of The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins, 2009, Scholastic Books (Teen Fiction/ Fantasy/ Adventure)

Against all odds, sixteen-year-old Katniss Everdeen won the Hunger Games, the forced battle-to-the-death between twenty-four children from the twelve districts of Panem (the nation formerly known as the United States of America). The Capital holds the Hunger Games every year to remind its citizens of a long-ago failed rebellion, and to make sure the people know exactly who is in charge of not only their lives, but their children's lives as well. Now that she's won, Katniss wants nothing more than to get back to ordinary life, living with her mother and sister and hunting with her stoic friend Gale. But Katniss' win was too unconventional to go unnoticed. To save herself and Peeta, the boy from her district who was also chosen to compete, Katniss pretended to fall in love with Peeta, and that lie broke all the rules. Now Katniss has the attention of the Capital officials and the long-suffering people, and both sides are waiting to see what Katniss will do next. Will she toe the Capital line to ensure the safety of her friends and family, or will she use her rebellion in the Games to spark something bigger? Katniss herself has no idea, but a heart-wrenching tour of the outlying districts and a horrific surprise from the Capital will make up her mind if nothing else does. Catching Fire is the second book in author Suzanne Collin's new trilogy. The first book, 2008's The Hunger Games, focused on Katniss' desperate and action-packed fight for survival. Catching Fire picks up where The Hunger Games left off and opens the story up from the stadium of the Games to the ins and outs of the larger world outside, with a detailed and suspenseful focus on the politics of this under-the-thumb dystopian world. Catching Fire is just as thrilling and gripping as The Hunger Games and with even more to think about. We can only wait with breaths held for the third book to find out how Katniss' superbly told fight turns out.

Almost twenty years after The Handmaid’s Tale, critically-acclaimed author Margaret Atwood revisits dystopian fiction with Oryx and Crake. This time, a lone man survives in a post-apocalyptic world along with a tribe of human-like super-beings. A former resident of the high-tech corporate gated communities, Jimmy (now calling himself the Snowman after that other lonely, isolated, abominable creature of the past) spends his days avoiding bio-hazards and genetically engineered predators, scavenging for supplies from the RejoovenEsence compound, and watching over the peaceful Children of Crake. Slowly, as he struggles to survive in this not-so brave new world, Jimmy reveals the story of his childhood friend Crake, a genius of genetics even at the age of eight; Oryx, the sexually-exploited girl Jimmy and Crake both obsessed over; and how the three of them brought about the creation of a new species and end of the mankind. It’s a compelling mystery, supported by horrific details of the biotechnology-obsessed world that flourished before Crake’s work brought about its collapse. Bleak though this world is, we’re in excellent hands with Margaret Atwood’s superb sense of satire, dark humor, and eerie realism. Atwood seems to be dreaming of dystopia again in her latest book, 2009’s The Year of the Flood, and by all reports it too is a finely wrought, provocative work of “what if?”

The House of the Scorpion is a hard world of drug lords, lost boys, computer implants, and clones. Between the U.S. and the nation formerly known as Mexico lies Opium, a country covered in poppy fields and ruled by the ruthless drug lord Matteo Alacrán, better known, because of his great age and power, as El Patrón. El Patrón keeps his country, his “eejits” (servants who have microchips in their brains to keep them slaving away without question), and his extensive family well under his thumb. El Patrón also has clones. Most clones get the numbing-and-dumbing brain chip, but not El Patrón’s. The newest Matteo Alacrán—young Matt—gets to grow up with a normal intelligence, though not, he soon learns, with a normal anything else. Clones are unnatural, lower than animals, inhuman monsters. But there are people who love Matt—Celia, the maid who raises him; Tam Lin, the bodyguard appointed by El Patrón; and María, a little girl who’s too young, innocent, and stubborn to let the usual prejudices guide her. Matt is occasionally called to the side of El Patrón and showered with gifts from the old man, but he’s mostly left to face the cruelty of the Alacrán family. Even when Matt discovers the truth about the real reason for his existence, escape is no guarantee of freedom. There are more trials to face, prejudices to overcome, a past to atone for, and a future that is uncertain to say the least. A Newbery Honor book, a National Book Award winner, and a recipient of the Printz Award for Young Adult Literature, this is work of fiction that borders uneasily on fact. There’s no guarantee that author Nancy Farmer has imagined a future that couldn’t really happen, which makes The House of the Scorpion a disturbingly addictive read.

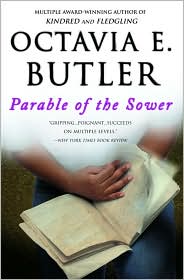

The year is 2025, and it’s hard to believe that life anywhere on earth could get worse. Massive environmental disasters and unchecked socioeconomic decline have turned the once-prosperous United States into a third world country complete with every imaginable aspect of suffering that entails—government as good as nonexistent, jaded law enforcement, unemployment, poverty, starvation, gang violence. The only relatively safe havens are small communities that build barricades around their streets to protect themselves from the rampant crimes of theft, rape, and murder that lie outside their locked and barred gates. Lauren Olamina, teenage daughter of a Baptist minister, lives with her family in one such walled community in southern California. It’s a close-knit place for its day; the people don’t have much but they can afford to band together, trade supplies, and watch each other’s backs. Lauren, however, is convinced the relative comfort that the neighborhood walls provide won’t last. Things on the outside are getting worse and people are becoming more desperate with every passing year--constant violence, extreme poverty, no water, not a job for miles. There’s even a new high-tech drug nicknamed “pyro” for the arsonist urge it compels in those who abuse it. Lauren is determined that when the time comes and the walls fail, she will be one to survive at any cost. It’s extraordinarily rare in Lauren’s world to meet an individual whose life has not been marred by suffering and loss, but Lauren has a personal philosophy that she calls Earthseed to get her through the pain-filled days. Instead of putting her trust in her father’s religion, Lauren’s God is the only constant in life: Change. Lauren records the discovery of her new faith along with the events of her life in a journal that provides the narrative format for Parable of the Sower. Reading the contents of Lauren’s diary is not always easy. The events of author Octavia E. Butler’s twenty-first century are more tragic than triumphant, but the reader has a reliable and capable narrator in young Lauren who, despite the horrors she endures, is always secure in her belief of a better future. Butler is a highly lauded author (the first science fiction writer to receive a MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant and one of the few African American sci-fi writers) who pens her tales with a direct simplicity and grace that is appealing and inviting to readers of all genres. This finely wrought warning of a very possible future continues in a compelling sequel, Parable of the Talents.

Titus and his friends go to the moon for spring break. They drive futuristic “upcars.” And they’re connected twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week to their feeds, computer implants that work like a high-tech hybrid of television, ipod, and Internet, directly networked to their brains. The feeds tell them what products to buy. The feeds play music and games. World news is vastly outnumbered by commercials. Titus rarely speaks—he can “chat” with others through his feed—but when he does, it’s with a raw, hesitant, barely legible slang. Even the few news reports about war and toxic waste are instantly forgotten in a blare of consumerism and consumption. Then Titus and his friends go to a club (on the moon, of course) where a hacker damages the party-goers’ feeds. Recovering in the hospital--and temporarily unplugged--Titus meets Violet, a strange girl even for this bizarre world. Violet has been brought up to pay attention to the events around her. She notices cause and effect, listens to more news reports than commercials, and even turns her feed off once in awhile. Titus is attracted to Violet, and even begins to question, in his own tentative and uncertain way, the issues and problems that Violet points out. But when Violet’s feed proves irreparable (or is it just too risky to save the rebellious Violet?), Titus is not exactly equipped to handle his emotions well. Author M.T. Anderson’s satire of the future is distinctly damaged and hopelessly empty. There’s a pretty clear cautionary tale here, but it’s the story of an acquisition-obsessed society that rings all too true. The audiobook version of Feed is a compelling way to experience the novel, with the voiced narration mimicking the commercial interruptions of the all-too invasive feed.

Uglies by Scott Westerfeld, 2005, Simon Pulse Books (Teen Fiction/ Science Fiction)

Uglies by Scott Westerfeld, 2005, Simon Pulse Books (Teen Fiction/ Science Fiction)

The world of Uglies seems pretty ideal. The future is a place without war, racism, or environmental destruction. Even better, everyone is physically beautiful and their only job is to have fun. Ready for the catch? Up to the age of sixteen, people are ugly. At least, they’re taught to believe that the faces they’re born with are ugly. On their sixteenth birthday, everyone undergo a mandatory cosmetic surgery that reshapes their bones, widens their eyes, perfects their physiques, and makes them all conform to an ideal standard of beauty. Then they’re sent to New Pretty Town to party all day and all night, with nary a care for the rest of their lives. Tally Youngblood is an almost-sixteen-year-old ugly who can’t wait to be remade as a partying pretty. But then she meets Shay, who criticizes the concept of beauty and questions the need for a surgery that, no matter how attractive it makes you, also removes any trace of the individuality that we’re all born with. Tally’s unconvinced, but then Shay runs off to a mysterious place called the Smoke where a band of non-prettied people live in harmony with nature and their natural-born looks. The very pretty, very scary officials from Special Circumstances come swooping down on Tally and offer her a terrible choice: If Tally doesn’t follow Shay to the Smoke and betray her to the authorities, they’ll never let her turn pretty at all. There are tough choices ahead for young Tally, but there’s a lot of fun for the reader—action scenes with hoverboards and bungee jackets, traces of our own modern-day society left in rusty ruins, and suspicions that there’s something much more sinister to being pretty than meets the eye. Uglies is a gripping page-turner, a cutting-edge social commentary with a killer cliffhanger ending to boot. Luckily, Uglies is the first of a series. Pretties, Specials, and Extras follow and pack quite the dystopian punch of their own.

No comments:

Post a Comment